Abstract

Background

Treatment at academic cancer centers (ACs) has been associated with improved outcomes across hematologic malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. ACs offer the benefit of high treatment volume in addition to enrollment in clinical trials, involvement in post-graduate education, and expanded access to diagnostic and treatment related services. Though studies on multiple myeloma (MM) have demonstrated a survival benefit with treatment at both high-volume centers and at NCCN designated cancer centers, this is the largest study to date examining the benefit of academic centers.

Methods

The National Cancer Database was utilized to obtain data on patients diagnosed with MM between 2004-2017 for which data on treatment facility type was available. Using the Commission on Cancer facility categories, patients treated at ACs were compared to those treated at non-academic centers (NACs), including small and large volume community cancer centers. Demographic and treatment characteristics were compared between centers, with median overall survival (OS) assessed by Kaplan Meier. Cox regression analysis was used to asses the HR for OS by facility type, and adjusted on multivariate analysis for age, sex, race, insurance, time to treatment, and use of autologous transplant.

Results

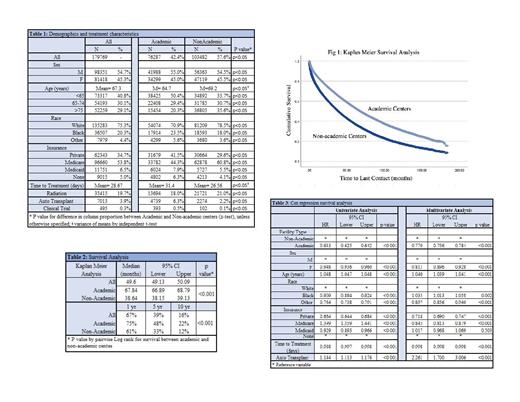

Of the 179,769 MM patients available, 42.4% were treated at ACs (p<0.05). Patients treated at ACs were younger than those treated at NACs (mean age 64.7 years vs. 69.2 years, p<0.05) and patients > 75 years of age were more often treated at NACs (35.6% vs. 20.3%, p<0.05). ACs were more likely to treat Black and other minority patients, with Black patients representing 23.5% vs. 18%, and other minorities 5.6% vs. 3.6% of patients treated at ACs vs. NACs, respectively; all p<0.05. Academic centers were more likely to treat uninsured patients (6.3% vs. 4.1%), patients on Medicaid (7.9% vs. 5.5%) as well as privately insured patients (41.5% vs. 29.6%),( all p<0.05). The majority of Medicare patients were treated at NACs (60.8%), p<0.05.

The time from diagnosis to treatment was longer at ACs, at 32.4 vs. 26.5 days (p<0.05), and patients were more likely to receive autologous stem cell transplant as first line treatment at ACs (6.3% vs 2.2%, p<0.05). While clinical trial data is limited in the NCDB, the majority of the 495 patients treated under a clinical trial were treated at ACs (393 vs 102, or 0.5% vs 0.1% of patients treated at ACs vs NACs, p<0.05).

Median OS at ACs was significantly longer than at NACs, with median OS of 67.8 months (95% CI 66.89-68.79 months) compared to 38.6 months (95% CI 38.15-39.13 months) at NACs, p<0.05. One year OS was 75% vs 61%, 5-year OS 48% vs 33%, and 10-year OS of 22% vs 12% at ACs vs NACs, respectively; p<0.05. When adjusted for age, gender, race, insurance, time to treatment, and use of autologous transplant on Cox Regression analysis, the improvement in OS remained. Patients treated at AC had hazard ratio of 0.77 for all-cause mortality (95% CI 0.756-0.784) when referenced to NACs on multivariate analysis (p<0.05).

Conclusion

Patients with MM had significantly improved survival when treated at academic centers compared to all other facility types. The improvement in OS remained when controlled for available treatment and demographic features. Multiple factors, including specialized care, trial enrollment, and early access to autologous stem cell transplant may contribute to these improvements. Further investigations into the factors contributing to such disparities are required to standardize care and improve overall outcomes.

Tantravahi: CTI BioPharma: Research Funding; Novartis: Research Funding; BMS: Research Funding; Abbvie Inc.: Research Funding; Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc.: Consultancy, Honoraria, Research Funding. Sborov: SkylineDx: Consultancy; GlaxoSmithKline: Consultancy; Janssen: Consultancy, Membership on an entity's Board of Directors or advisory committees; Sanofi: Consultancy.